Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings Story

You can explore the story of Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings in the presentation and information below. Intrigued? Why not visit us or find out about volunteering to discover more.

Early Days

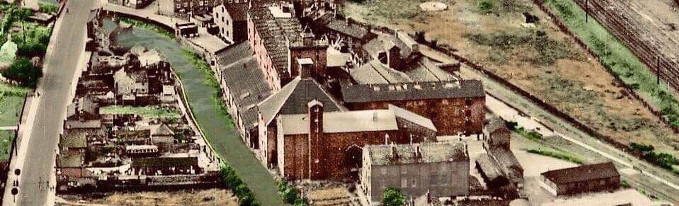

In 1796 John Marshall (1765-1845) and the brothers Thomas and Benjamin Benyon purchased a seven acre site in the hamlet of Ditherington within the suburb of Castle Foregate on the outskirts of Shrewsbury. Benjamin Benyon wanted to return from Leeds to his native town and the partners saw an opportunity to build a factory to twist thread in Shrewsbury. The nearby carpet weavers in Bridgnorth and Kidderminster provided a market for tow yarns, a by-product of thread-making from the mill.

The site was well-chosen. It stood close to the Bagley Brook which provided a water supply and it was only a few hundred yards from port facilities on the River Severn. Ditherington was also on a turnpike route from Shrewsbury to Whitchurch and Market Drayton. These means of transporting goods would allow raw materials and finished products to be moved to and from the factory. Moreover, the factory was built next to the route of the Shrewsbury Canal which had been authorised in 1793 by an Act of Parliament to enable coal to be moved from Oakengates to Shrewsbury more easily than by horse-drawn wagon along the Holyhead Road. The canal was opened in January 1797 and coal could be unloaded directly into the engine house at Ditherington Mill. The subscribers to the canal included local landowners, industrialists and professional men. They included Earl Gower, the industrialists John Wilkinson and William, Richard and Joseph Reynolds and Dr Robert Waring Darwin, a son of Erasmus Darwin, the father of Charles Darwin and a childhood friend of a partner in the Ditherington enterprise, Charles Woolley Bage.

In 1776, Charles Bage was living in Shrewsbury and by the 1780s he was a wine merchant in the town. In 1793 he was a liquor merchant in Pride Hill and had an account with Lord Clive. He also worked as a surveyor and it was presumably in this capacity that he came to the notice of John Marshall and the Benyon brothers as a potential colleague in their scheme to build a new mill. Marshall and the Benyon Brothers experienced a devastating fire at one of their mills in Water Lane, Leeds on 13 February 1796. The cost was estimated at £10,000, only half of which was met by insurance. Undoubtedly, they wanted a different mode of construction for a new fire-proof building. The mill in Shrewsbury provided this opportunity. Charles Bage had a great understanding of the structural properties of iron. This is revealed in various records, including his correspondence with the factory master, William Strutt in Derbyshire who shared his interest in iron construction, his discussion in 1801 of Thomas Telford’s design for London Bridge and the building of the pioneering iron-beamed mill at Ditherington.

Charles Bage, the Flax Industry and Shrewsbury’s Iron-Framed, Malcolm Dick.

Fabulous Flax

Flax has been grown for thousands of years. The seeds of the Flax plant produce linseed oil. The seeds and husks are used for animal and human consumption, and the fibrous stem of the plant to make linen thread, fabric and rope. Flax is planted in the spring and takes 90 days to grow. It is broadcast or sown in rows. It will grow in sun or partial shade, which will affect the colour and texture of the linen and has beautiful blue flowers. Flax is pulled from the ground before the seeds ripen, rather than cut. Pulling retains the full length of the flax fibres which extend to the root of the plant. Traditionally, the pulled flax was either tied in bundles and soaked in water (retted) or laid out in the field for the dew to ret. Soaking the flax in water broke down the pectins surrounding the fibres, allowing them to be freed from the stalk. Water-retting often took place in pits. After retting, the flax was tied into stooks or bundles and laid out in the fields to dry. Shewsbury Flax Mill imported flax from English growers, the Low Countries, Ireland and Russia.

When dry, the seeds were rippled off with a metal comb. The outer and inner straw, called ‘shives’ was removed with a flax breaker, which broke the straw into small pieces. These were then ‘scutched’ or scraped from the fibres. The fibres then needed to be separated into long and short fibres. This was done by ‘hackling’ or ‘heckling’. Hackles were a series of metal combs. The long fibres, or line, would make good quality linen, whilst the short fibres, called tow, would be used for rough cloth and rope. Shrewsbury Flax Mill brought in fibres ready for hackling. Soon after the construction of the Main Mill the Cross Mill was added to house the hackling process. The hackling at Shrewsbury Flax Mill was done by hand until 1811, when eleven hackling machines were introduced. In some hackling machines the tow would have to be extracted from the hackle pins, and this task would often be done by small children. In addition to working with sometimes dangerous machinery, all the workers were exposed to dust inhalation.

Spinning twists the thread to make it stronger for use in weaving or knitting. The spinning of wool, hemp, flax and latterly cotton took place in domestic settings until several major inventions revolutionised the spinning process. The invention of the spinning jenny in 1764 by James Hargreaves and the water frame by Sir Richard Arkwright in 1769, had a great social impact. Large Mill towns developed employing thousands of men, women and children.

John Marshall pioneered the industrial spinning of flax. The earliest flax spinning machinery spun the flax dry, generating a great deal of dust. Wet spinning was introduced In the 1830s, this involved drawing the fibres through a trough of hot water during the spinning process. The dry, dust laden atmosphere during spinning was replaced by a humid one, equally as bad for the workers’ health.

When Shrewsbury Flax Mill was built in 1797, it housed 900 spinning and twisting spindles. Both line and tow were spun into yarn and thread for weaving and sewing. Shrewsbury Flax Mill employed over 400 people in 1813 and over 800 by 1845. The mill was the largest employer in Shrewsbury and a successful and profitable producer of thread. Flax dressing at the site ended in the 1850s, and the site was switched to finishing the thread and yarn produced at the Marshall’s Leeds premises.

Textile mills needed large windows to let in light for the spinners to work by. When Shrewsbury Flax Mill became a Maltings in 1896-7 many of the windows were blocked to provide a dark space for the barley to germinate.

Until 1856, when William Perkin patented chemical dyes, coloured dyes would have come from plants and minerals, with these being mainly imported. Colours such as purple were very expensive. Before weaving, yarn would be boiled in lye and wood ash to whiten it. Later, chemical bleaches were used. The woven cloth was laid out in “bleach fields” to lighten the colour. In 1811 Marshall purchased a water mill in Hanwood to be used as a bleach works for the Shrewsbury Flax Mill. Shrewsbury Flax Mill had its own large Dye & Stove House, originally built in 1803 and substantially rebuilt in the 1850s. The Hanwood bleach works was considerably expanded in the 1850s & 1860s. These developments reflect the increase in bleaching and dyeing that arose when Shrewsbury Flax Mill became a finishing mill.

Workers at the Flax Mill

The Flax Mill factory was employing apprentices from as early as 1802. It is though that there were 800 employees in the early 1840s. The census of 1851 shows that 55% of the 377 workers in that year were aged 20 or younger, 33% were under the age of 16. The present Apprentice House was built in 1812 to house workers. Inside male and female apprentices were kept segregated. The Benyons took seriously the welfare and moral upbringing of their younger employees. John Marshall who owned the mills, in Leeds as well as Ditherington is known to have treated his workers better than most factory workers, forbidding corporal punishment and installing fans to regulate the temperature. However the testimony of brothers Samuel and Jonathan Downe to the Parliamentary Committee of 1832 tells a very different story. When asked about his treatment during his employment at Mr Marshall's mill in Shrewsbury, Samuel Downe replied:

'Strapped? Yes, I was strapped most severely till I could not bear to sit upon a chair without having pillows, and I was a forced to lie upon my face in the night-time at one time, and through that I left; I was strapped both on my own legs, and then I was put upon a man’s back, and then strapped and buckled with two straps to an iron pillar and flogged, and all by one overlooker; after that he took a piece of tow, and twisted it in the shape of a cord, and put it in my mouth, and tied it behind my head.'

Ditherington Flax Mill ceased production due to the competition from mills in Leeds. The mill was sold to William Jones Maisters (Ltd) who adapted the building for use as a Maltings factory in 1897.

Adaptation of the Mill

There is much evidence, both inside and outside of the buildings, showing how they were adapted for Malt production. For example, holes were cut in the floor to hold cone shaped hoppers, concrete floors were laid, large tanks to ‘steep’ or wet the barley were installed, the prominent timber hoist tower, with its ornamental capping to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, was constructed. The malting process demanded controlled daylight and ventilation so that two thirds of the windows were blocked off and smaller windows with shutters were inserted. A Malt Kiln was also constructed on the site in 1898.

Making malt from barley corns is the first stage of the brewing process. Barleycorns are left in cold water, usually for two days before being moved and spread in thin layer across germination floors. Each batch would be periodically tuned by hand, using a wooden malt shovel. After sufficient germination, when the starch within the barleycorn has been partially converted to malt sugars, the barley is dried and cured by heat treatment in the Malt Kiln stopping the process.

William Jones Malsters (Ltd) went bankrupt in 1934. Since then the site has been used as a Light Infantry Barracks during the Second World War, and again for malting production (Ansells) from 1948 until closure in 1987.

We, the Friends of the Flaxmill Maltings, are celebrating 10 years since our formation in August 2010.

Working in partnership with the site’s owners, Historic England, we have been vital in developing the vision to bring this site back to life. We’ve led the way in engaging the community and helping people to learn more about the historic buildings and their former uses, as well as getting to know the people who lived and worked here.

The Friends of the Flaxmill Maltings came about because local councillor, Alan Mosley, believed that a local group able to inform, involve and engage with the local and wider community would greatly strengthen bidding projects and he was proven right. A public meeting resulted in a committee made up of local people and later a trust with company and charity status with Alan as Chair.

In the 10 years since, our hard-working volunteers have generously given over 17,000 hours of their time to the project. This has included hosting popular tours and talks, managing the existing Visitor Centre, overseeing education programmes, hand stitching garments, art projects, organising Heritage Open Days and Family Fun Days, and researching the history. Our work has gained great public acclaim.

Update on the restoration

The Stage 2 project at Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings, which has received National Lottery funding of £20.7million from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, will restore the Grade I listed Main Mill - the first cast-iron framed building in the world and forerunner to the modern skyscraper, and the Grade II listed Kiln along with landscaping and a new car park. This is managed by site owners, Historic England. The upper four floors of the Mill will provide commercial office space. When complete there will be visitor experience on the ground floor which will be managed by us, the Friends of the Flaxmill Maltings, as well as a café.

Work began on 19 June 2017, carried out by Croft Building and Conservation Ltd. Croft has carried out structural repairs to the Main Mill and reintroduced windows that were blocked up during the Maltings phase. This has flooded the building with natural light. Work is nearing completion to repair the Kiln and Engine Houses at either end of the Main Mill. In 2020 the Jubilee Tower, coronet, water tank and bell cote have been restored and are all now visible from across the town. Following this work, the final phase will be the internal fit out of the buildings.

The main works will be finished in autumn 2021, when the restored upper four floors of commercial space will be available for letting creating approximately 28,000 square feet of unique commercial space. Work on the fit out of the interpretation on the ground floor of the Main Mill will continue and this space will open to the public in spring 2022.

To find out more about the restoration of the Main Mill and Kiln, plans for the wider site, the other buildings and the brownfield land surrounding the site, please visit Historic England where there is lots of up to date information.

Outline planning consent permitting housing on the undeveloped brownfield land surrounding Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings, including the Apprentice House, was granted in 2011. This is now due to expire and Historic England are applying to renew this consent (December 2020). Historic England knows that there is lots of public interest in this element of the scheme so have provided answers to the most frequently asked questions here if you would like to find out more.

Update on the visitor experience

We, the Friends, are currently involved in collaborative work with Historic England and The National Lottery Heritage Fund to provide a world-class visitor experience on the ground floor of the Main Mill. There will also be a café which will be open to tenants, visitors and the local community. The Friends will manage the café partner when appointed.

The highly respected Mather & Co were appointed in late 2020 to design and build the visitor experience at Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings in close collaboration with the Friends.

Our future work will also involve comprehensive tours around the site to suit all visitors and an exciting events, exhibitions and activities programme. Working to provide programmes for schools will be a priority as will further research into the colourful history of the site and those who worked there. Our vision is that the renovated site will not only be a centre for visitors but will also provide activities for the local and wider community.

Obviously, none of this would be possible without the enormous contribution which has and will continue to be made by our enthusiastic and hardworking volunteers. We are continuing to welcome volunteers to our ranks; if you are interested to join, please get in touch.